Vienna Media News – March 2023

The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair in 25 Pictures.

March 9, 2023 - The 1873 World’s Fair turbocharged Vienna’s transformation into a truly global city. It was the driving force behind the Austrian capital’s emergence as an international center. Here we take a journey back in time to 1873 using period images that bear witness to the past – from photographs (after all, this was the first World’s Fair to be comprehensively caught on camera), illustrations and prints to caricatures and maps. Together, they paint a historical picture of the strange goings on, scandals and sensations of the time, with fun facts, highlights and some amazing World’s Fair stats thrown in for good measure.

In 1873, the Rotunda building in the center of the Palace of Industry section of the Expo was the largest domed structure in the world. Hyped as the “eighth wonder of the world” at the time, it was twice the size of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome with a span of 108 meters! The Viennese, however, took a dim view of the building to begin with, slating it as a “tin pile”, “Bundt cake” or “cheese bell”. And it leaked whenever it rained. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

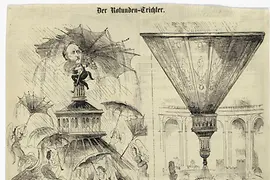

The imperial crown on the very top of the Rotunda measured 4 meters and weighted 4 tonnes. The roof was supported by 32 iron columns, and the iron structure tipped the scales at 4,000 tonnes. The Rotunda had a capacity of 27,000 visitors. Unfortunately, they got wet whenever it rained because the building leaked. Something eagerly seized upon by caricaturists. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Precisely 206,270 visitors lapped up the views of Vienna from the roof of the Rotunda building where they could enjoy the scenes through large, fixed telescopes. Anyone who paid admission was allowed to use the stairs, and later the hydraulic elevator located inside one of the iron support columns. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

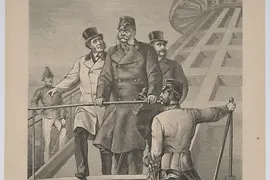

Wilhelm, the German Emperor, was one of countless visitors to take to the roof of the Rotunda. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Taking the Rotunda down after the fair would have been a costly business – so it remained in place, becoming another Viennese landmark after St. Stephen’s Cathedral, until it was engulfed in flames on September 17, 1937. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Bankruptcy, bad luck and bungles: it was with a pervading sense of euphoria that the Viennese went about organizing the largest world exhibition to date. But the combined effects of a stock market crash, a cholera epidemic, extended periods of bad weather and high admission prices (tickets for the grand opening cost 25 guilders – enough for a working-class family of four to live off for three weeks) put a serious dampener on proceedings. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The final figures: rather than the 20 million visitors expected, just 7.3 million had passed the turnstiles by the time it closed on November 2, 1873 . Total costs: 19,123,270 guilders and 80 kreuzers; revenue: 4,256,349 guilders and 55.5 kreuzers. The verdict: bad for the state coffers, priceless in terms of urban development. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

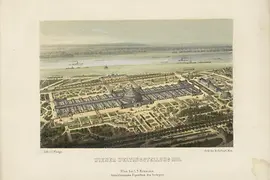

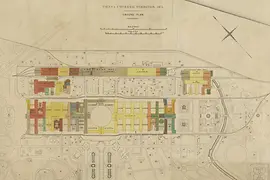

Vital statistics: the fifth World’s Fair in history and the first ever in the German-speaking world, Vienna’s international expo outdid its predecessors in terms of exhibition space (at 116,342m², it was twelve times the size of London’s 1862 venture). 35 sovereign nations and 53,000 exhibitors participated. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The art section included the 7,000m² Kunsthalle, an exhibition hall where virtually every inch of wall space was plastered with art, as well as two smaller pavilions (the only buildings from the World’s Fair to survive) and the Kunsthof courtyard area. Pride of place was given to 6,600 works of art created since the London expo of 1862. The majority of which hailed from France. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

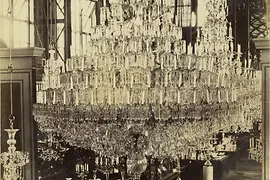

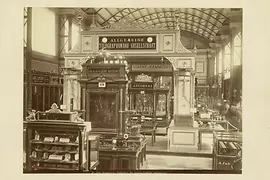

Products from the traditional crafts and trades were also a huge hit at the World’s Fair: specialist manufacturers such as Lobmeyr (crystalware, including a magnificent chandelier) and Jarosinski & Vaugoin (silver) picked up highly coveted medals for their work. Both of whom continue to fly the flag for Viennese craftsmanship to this day. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

It was in Vienna that Japan showcased itself to the world on a grand scale for the first time. The “Japonism” that this inspired left its mark on Western art (above all Gustav Klimt) and craft. And the soybean brought to the capital by the Japanese World's Fair delegation spread from Vienna all over the world. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

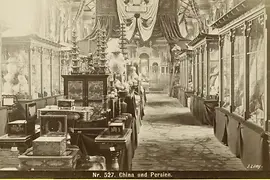

The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair was the first to feature Japan – and the first to welcome notable contributions from Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, the Ottoman Empire and Persia. This photo provides insight into the China and Persia department’s collection. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Royal rendez-vous: Emperor Franz Joseph visited the exhibition a total of 48 times. In all, some 33 high-ranking members of the global aristocracy were on the guest list, including the Russian tsar, the German emperor and the Italian king – and, sensationally, the Shah of Persia, Nāsir al-Dīn on August 3, 1873. The sounds of Johann Strauss II’s Persian March at the fair earned the composer the Persian Order of the Sun. But it wasn’t all rainbows and sunshine: Laxenburg Palace where the Shah and his 60-strong entourage stayed was left in a dire state and in need of repairs after they left! | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Exhibits from Britain included slate, coal, ores, minerals and paper curtains. The biggest draw was the jewelry of Victorian socialite Georgina Dudley, estimated to be worth an eye-watering 25,000 pounds sterling. Never solved, the theft of the jewels in the Paddington Station heist of December 12, 1874 would go down in criminal history. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The Trieste Maritime Authority presented a warning system consisting of a lighthouse, optical telegraph and foghorn. Every evening, the latter signaled the end of the exhibition with three loud, drawn-out notes – to the horror of the visitors on the lighthouse’s terrace and the annoyance of the people attending the concerts at the music pavilion. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

On the opening day of the World’s Fair, 10,567 telegrams were sent from Vienna’s telegraph station. The longest comprised 4,555 words. Telegraphs were also showcased at the exhibition itself. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Even a whistlestop tour of everything on show was simply not possible in just one day: viewing all the exhibits properly would have taken somewhere in the region of 40 days. The guide to the event in the exhibition newspaper Die Internationale Ausstellungs-Zeitung recommended taking a systematic approach; and it also suggested that its readers use a notebook and try to exercise a certain pragmatism. “Anyone looking to see plenty will end up seeing nothing”, it cautioned. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

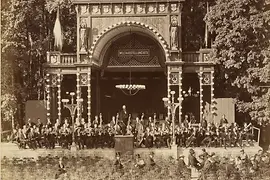

Johann Strauss II managed to secure exclusive performance rights for the World’s Fair site for his World’s Fair Orchestra. Although the acoustics in the Rotunda proved to be poor, the ensemble played on, enjoying only moderate success. In the hastily-erected music pavilion, only the musicians were sheltered from the elements, ticket prices were high, and Strauss rarely deigned to pick up the baton himself. However, Strauss managed to swing public opinion in his favor thanks to the concerts he gave outside the World's Fair site. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

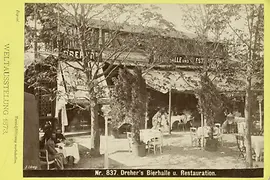

Visitors to the fair could take a culinary trip around the world as there was a huge variety of food and drink on offer (pictured here is Dreher’s Bierhalle), but the exorbitant prices, paltry portions and questionable quality caused an uproar. The actor János Szika, for example, complained that he was served a chicken in the English restaurant that “had abandoned all hope of ever being eaten and had simply slipped over to a state of decay.” Whereupon he “dashed the thing onto the floor". | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

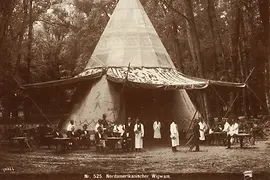

One of the more unusual catering establishments was the Wigwam. Strange as it was, New York operator Boehm & Wiehl’s idea struck a chord with fairgoers: the bar was a huge hit, especially the cocktails (such as the Sherry Cobbler, Mint Julep and Catawba Cobbler), which – in a complete novelty for Austrians – were sipped through straws. And it was here that performers danced to the song Yankee Doodle for the five-year-old Archduchess Marie Valerie. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Another curiosity was the fleet of 500 wheeled chairs produced by company Fischer & Meyer to help people get around the exhibition site. Available for rent, they were piloted by elegantly liveried drivers. Clearly impressed, the imperial court went on to commission its own set. Shown here is a stereo photo which would have been viewed through a stereoscope to create the perception of depth – cutting-edge for the time. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

At the beginning of July 1873, the Oesterreichische Bergbahn-Gesellschaft opened a funicular railway – in fact, another World’s Fair exhibit – on the Leopoldsberg hill near Vienna. About every ten minutes, two cars, each with a capacity of 100 passengers, traveled uphill and back downhill covering a difference in elevation of 242 meters. The ride lasted about five minutes. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

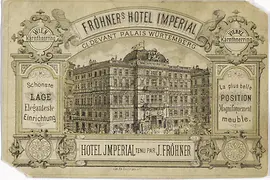

It was hoped that the World’s Fair would attract up to 20 million visitors – as many as 30,000 each day. Numerous hotels were built, including the elegant Hotel Imperial (originally a mansion house commissioned for Duke Philipp von Württemberg), which is still in operation today. It was the only hotel in the Austrian Empire that was allowed to use the designation K. k. Hofhotel confirming its status as holder of an imperial warrant. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

On October 24, 1873, the First Vienna Mountain Spring Pipeline was opened. To this day fresh drinking water continues to flow through it directly to Vienna from the Alps 95 kilometers away. Its completion was marked by the opening of the Hochstrahlbrunnen fountain – by Emperor Franz Joseph – a landmark visible far and wide in the city. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The work of the exhibition’s jurors was every bit as taxing as it was brimming with responsibility. After all, somewhere in the region of 30,000 bottles of wine and 60,000 liqueurs and brandies had to be judged. Among the 25,572 awards were 8,687 medals of merit, 2,929 medals for significant advancements, 2,162 medals for employees, 977 art medals, 310 medals for good taste, 10,066 diplomas of recognition, and 441 honorary diplomas. The prizes were awarded in a ceremony held on August 18, 1873, which just so happened to be the Emperor’s birthday. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

In 1873, the Rotunda building in the center of the Palace of Industry section of the Expo was the largest domed structure in the world. Hyped as the “eighth wonder of the world” at the time, it was twice the size of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome with a span of 108 meters! The Viennese, however, took a dim view of the building to begin with, slating it as a “tin pile”, “Bundt cake” or “cheese bell”. And it leaked whenever it rained. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The imperial crown on the very top of the Rotunda measured 4 meters and weighted 4 tonnes. The roof was supported by 32 iron columns, and the iron structure tipped the scales at 4,000 tonnes. The Rotunda had a capacity of 27,000 visitors. Unfortunately, they got wet whenever it rained because the building leaked. Something eagerly seized upon by caricaturists. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Precisely 206,270 visitors lapped up the views of Vienna from the roof of the Rotunda building where they could enjoy the scenes through large, fixed telescopes. Anyone who paid admission was allowed to use the stairs, and later the hydraulic elevator located inside one of the iron support columns. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Wilhelm, the German Emperor, was one of countless visitors to take to the roof of the Rotunda. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Taking the Rotunda down after the fair would have been a costly business – so it remained in place, becoming another Viennese landmark after St. Stephen’s Cathedral, until it was engulfed in flames on September 17, 1937. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Bankruptcy, bad luck and bungles: it was with a pervading sense of euphoria that the Viennese went about organizing the largest world exhibition to date. But the combined effects of a stock market crash, a cholera epidemic, extended periods of bad weather and high admission prices (tickets for the grand opening cost 25 guilders – enough for a working-class family of four to live off for three weeks) put a serious dampener on proceedings. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The final figures: rather than the 20 million visitors expected, just 7.3 million had passed the turnstiles by the time it closed on November 2, 1873 . Total costs: 19,123,270 guilders and 80 kreuzers; revenue: 4,256,349 guilders and 55.5 kreuzers. The verdict: bad for the state coffers, priceless in terms of urban development. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Vital statistics: the fifth World’s Fair in history and the first ever in the German-speaking world, Vienna’s international expo outdid its predecessors in terms of exhibition space (at 116,342m², it was twelve times the size of London’s 1862 venture). 35 sovereign nations and 53,000 exhibitors participated. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The art section included the 7,000m² Kunsthalle, an exhibition hall where virtually every inch of wall space was plastered with art, as well as two smaller pavilions (the only buildings from the World’s Fair to survive) and the Kunsthof courtyard area. Pride of place was given to 6,600 works of art created since the London expo of 1862. The majority of which hailed from France. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Products from the traditional crafts and trades were also a huge hit at the World’s Fair: specialist manufacturers such as Lobmeyr (crystalware, including a magnificent chandelier) and Jarosinski & Vaugoin (silver) picked up highly coveted medals for their work. Both of whom continue to fly the flag for Viennese craftsmanship to this day. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

It was in Vienna that Japan showcased itself to the world on a grand scale for the first time. The “Japonism” that this inspired left its mark on Western art (above all Gustav Klimt) and craft. And the soybean brought to the capital by the Japanese World's Fair delegation spread from Vienna all over the world. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair was the first to feature Japan – and the first to welcome notable contributions from Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, the Ottoman Empire and Persia. This photo provides insight into the China and Persia department’s collection. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Royal rendez-vous: Emperor Franz Joseph visited the exhibition a total of 48 times. In all, some 33 high-ranking members of the global aristocracy were on the guest list, including the Russian tsar, the German emperor and the Italian king – and, sensationally, the Shah of Persia, Nāsir al-Dīn on August 3, 1873. The sounds of Johann Strauss II’s Persian March at the fair earned the composer the Persian Order of the Sun. But it wasn’t all rainbows and sunshine: Laxenburg Palace where the Shah and his 60-strong entourage stayed was left in a dire state and in need of repairs after they left! | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Exhibits from Britain included slate, coal, ores, minerals and paper curtains. The biggest draw was the jewelry of Victorian socialite Georgina Dudley, estimated to be worth an eye-watering 25,000 pounds sterling. Never solved, the theft of the jewels in the Paddington Station heist of December 12, 1874 would go down in criminal history. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The Trieste Maritime Authority presented a warning system consisting of a lighthouse, optical telegraph and foghorn. Every evening, the latter signaled the end of the exhibition with three loud, drawn-out notes – to the horror of the visitors on the lighthouse’s terrace and the annoyance of the people attending the concerts at the music pavilion. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

On the opening day of the World’s Fair, 10,567 telegrams were sent from Vienna’s telegraph station. The longest comprised 4,555 words. Telegraphs were also showcased at the exhibition itself. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Even a whistlestop tour of everything on show was simply not possible in just one day: viewing all the exhibits properly would have taken somewhere in the region of 40 days. The guide to the event in the exhibition newspaper Die Internationale Ausstellungs-Zeitung recommended taking a systematic approach; and it also suggested that its readers use a notebook and try to exercise a certain pragmatism. “Anyone looking to see plenty will end up seeing nothing”, it cautioned. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Johann Strauss II managed to secure exclusive performance rights for the World’s Fair site for his World’s Fair Orchestra. Although the acoustics in the Rotunda proved to be poor, the ensemble played on, enjoying only moderate success. In the hastily-erected music pavilion, only the musicians were sheltered from the elements, ticket prices were high, and Strauss rarely deigned to pick up the baton himself. However, Strauss managed to swing public opinion in his favor thanks to the concerts he gave outside the World's Fair site. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Visitors to the fair could take a culinary trip around the world as there was a huge variety of food and drink on offer (pictured here is Dreher’s Bierhalle), but the exorbitant prices, paltry portions and questionable quality caused an uproar. The actor János Szika, for example, complained that he was served a chicken in the English restaurant that “had abandoned all hope of ever being eaten and had simply slipped over to a state of decay.” Whereupon he “dashed the thing onto the floor". | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

One of the more unusual catering establishments was the Wigwam. Strange as it was, New York operator Boehm & Wiehl’s idea struck a chord with fairgoers: the bar was a huge hit, especially the cocktails (such as the Sherry Cobbler, Mint Julep and Catawba Cobbler), which – in a complete novelty for Austrians – were sipped through straws. And it was here that performers danced to the song Yankee Doodle for the five-year-old Archduchess Marie Valerie. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

Another curiosity was the fleet of 500 wheeled chairs produced by company Fischer & Meyer to help people get around the exhibition site. Available for rent, they were piloted by elegantly liveried drivers. Clearly impressed, the imperial court went on to commission its own set. Shown here is a stereo photo which would have been viewed through a stereoscope to create the perception of depth – cutting-edge for the time. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

At the beginning of July 1873, the Oesterreichische Bergbahn-Gesellschaft opened a funicular railway – in fact, another World’s Fair exhibit – on the Leopoldsberg hill near Vienna. About every ten minutes, two cars, each with a capacity of 100 passengers, traveled uphill and back downhill covering a difference in elevation of 242 meters. The ride lasted about five minutes. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

It was hoped that the World’s Fair would attract up to 20 million visitors – as many as 30,000 each day. Numerous hotels were built, including the elegant Hotel Imperial (originally a mansion house commissioned for Duke Philipp von Württemberg), which is still in operation today. It was the only hotel in the Austrian Empire that was allowed to use the designation K. k. Hofhotel confirming its status as holder of an imperial warrant. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

On October 24, 1873, the First Vienna Mountain Spring Pipeline was opened. To this day fresh drinking water continues to flow through it directly to Vienna from the Alps 95 kilometers away. Its completion was marked by the opening of the Hochstrahlbrunnen fountain – by Emperor Franz Joseph – a landmark visible far and wide in the city. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

The work of the exhibition’s jurors was every bit as taxing as it was brimming with responsibility. After all, somewhere in the region of 30,000 bottles of wine and 60,000 liqueurs and brandies had to be judged. Among the 25,572 awards were 8,687 medals of merit, 2,929 medals for significant advancements, 2,162 medals for employees, 977 art medals, 310 medals for good taste, 10,066 diplomas of recognition, and 441 honorary diplomas. The prizes were awarded in a ceremony held on August 18, 1873, which just so happened to be the Emperor’s birthday. | Wien Museum: 1873 Vienna World’s Fair

–

© Wien Museum

Download print-ready version

More information about the Vienna World’s Fair in 2023 (News, Exhibitions etc.):

Sources:

Contact

Helena Steinharthelena.steinhart@vienna.info